The hammer in my hand

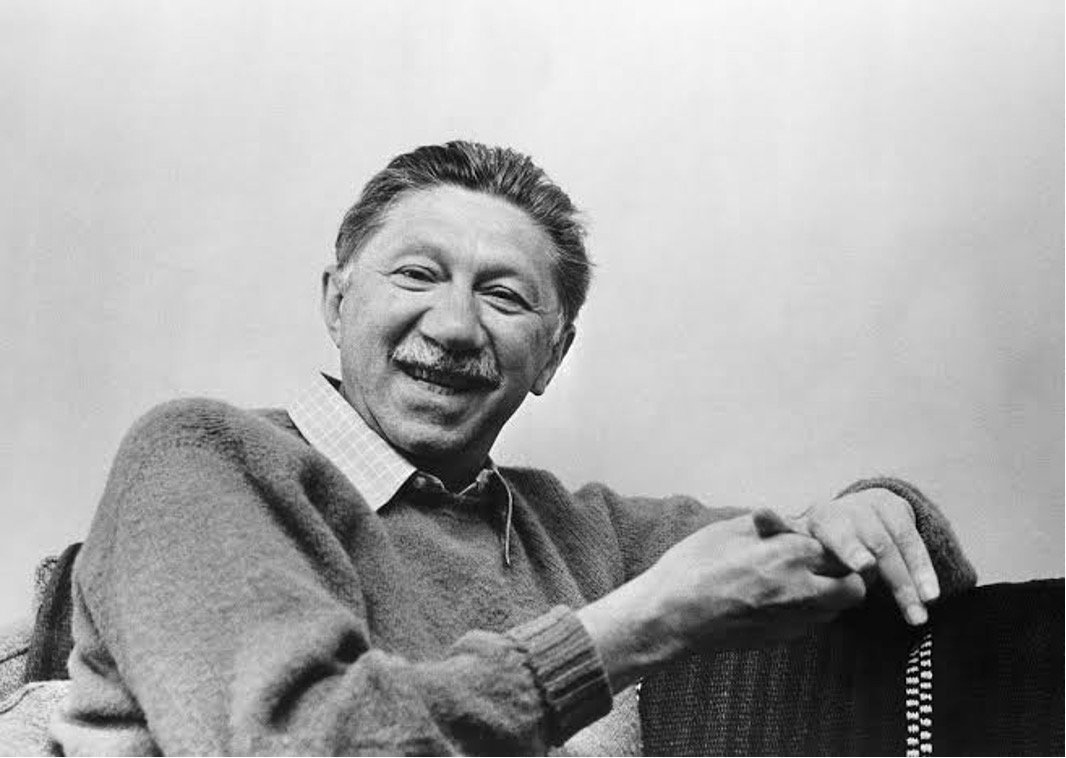

Abraham Maslow was a very smart guy. He is the one who created that hierarchy of needs pyramid.

Abraham Maslow, looking very smug after inventing the pyramid of needs.

Maslow once said something about tools that I often think about.

When I have a hammer in my hand, everything looks like a nail.

There is such a beautiful truth in this statement, that is incredibly relevant to the world we live in today.

Because there is a link between the tools we have and what we make.

Let me try to demonstrate this relationship by showing you some gadgets and tools that we use to make things.

Pentax 35mm stills camera

This looks familiar to you right? It is a camera.

Pentax 35mm film camera

But unlike the cameras you can buy today, it has no digital parts.

It is completely analog.

When you push the shutter down, the light that goes in through the lens is captured on film.

Compare it to the way digital cameras work, where the images are captured on a digital storage medium like a flash card. You can shoot thousands and thousands of images on one card. Whereas film cartridges hardly ever hold more than 36 exposures.

On top of that, film is relatively expensive and you have to either develop the film yourself and print the photos or have it done by somebody else. And on top of that, you can’t immediatey judge if you have the perfect shot.

On the surface, it seems that digital cameras are a huge improvement over digital. Who wants the limitation of 36 exposures? Who wants to wait days or weeks before seeing their image? It is no wonder that digital cameras have crushed the film competition.

But imagine this scenario: let’s say you are on holiday. You’re visiting new places together with friends or family. You want to capture something about your trip. Maybe you’re at a prominent touristic destination. With a digital camera, or even your phone, which also doubles as a digital camera, you can literally shoot limitless angles of the shot to make sure you get it.

With a film camera, you have to conserve the exposures. You have to be sure the light is right. You need to really think about the framing. Before you press down on the shutter.

You have to think. You have to think. You have to think.

Arriflex 16mm motion camera

Here is another camera.

It is the video version of the Pentax.

Arriflex 16mm film camera

When I was young, and we had to walk 16 miles barefoot in the snow to the agency, we used these types of cameras to shoot TV commercials. This 16mm camera and its bigger 35mm equivalents were heavy and used spools of very expensive film to capture the shots of a commercial or film.

Today, like with digital stills cameras, high fidelity digital motion cameras can shoot almost unlimited takes.

Digital cameras shoot on hard drives. These film cameras, shoot on film.

But again, with the older analog cameras, you had to be really prepared before shooting. You have to rehearse, over and over, getting the performances perfect. You have to be absolutely sure the lighting is correct and you, as a director have to think about your composition, the exposure and the film speed.

Shooting slow motion means shooting around 50 frames per second which means a roll of film can spool through a camera in less than a minute. Then. Reload with another spool.

As a production crew, you normally only order limited spools per shooting day. So if you spend too much on one shot, you severely limit your options later in the day.

You have to plan. And think.

Reel to reel film editing station

This is a reel to reel film editor.

Not like Instagram reels. But big wheels from which rolls of celluloid would spool.

Before digital editing software became commonplace, editors used these kinds of machines to edit films.

To cut a film, you had a supply reel on one side, and an uptake reel on the other. So when you were making your assembly, you’d spin the supply reel backwards and forwards, looking for the next shot in the sequence. It was a manual process and you had to look at all the shots to find the one you’re looking for.

Today, in non-linear systems like Premiere or Final Cut, the shots are individual video clips that can be tagged, named and sorted before you even start cutting. So when you’re looking for the next shot in your assembly, you don’t have to look at all the shots. You just have to look at the file names.

What happened in the reel to reel process is that in the moments when you were looking for the shot you had in mind, you’d find other shots you may have forgotten about. And in your subconcious you develop a better overall concept of what was in all your rushes, which of course gives you the possibility of making a deeper and richer cut.

Reel editing of course, like with typewriters, was also very mechanical process. The reels would be actual celluloid and when you wanted to make a cut, you had to use … get this … a razor.

And when you made a mistake, or someone asked for a change, you had to glue the film back together in exactly the right place.

The Royal 2B Typewriter

The Royal 2B Typewriter

Here is one of my favourite tools. The mechanical typewriter.

This machine uses no electricity.

It only has mechanical parts that require the downforce of your fingers to activate a series of hammers inside it to slam on a ribbon between the hammer head and the paper to make an imprint of the letter.

Compared with a modern computer, where if you make a mistake, you can just the backspace key and you try again.

With a typewriter like this, you’d have to tear out the page and start again.

Imagine, you are writing a manuscript for a novel and on a page you write hundreds of words. And as you get to the bottom you write a word and realise seconds later you could have used a better one.

There is no backspace key. Maybe there is a chemical solution to erase the error, but it is messy.

So you tear out the page and start again.

What is the consequence on the process? You think before every sentence. Or, you write some samples with a pencil on a notepad before you write it down. You craft the phrases, the sentences, the paragraphs and the chapters.

Your text is different to what it would have been on a computer.

Why? Because you have to think before you type.

The limitation of the tool

I hope you are starting to see the point I am making.

Some tools, by their nature, have a limitation. But the limitation can have a positive effect on the product that you are making with that tool.

And before you ridicule me as an old man who is overly nostalgic: let me say this. The advent of digital has given us incredible tools. In fact, I don’t think I would not be where I am today, doing my job, and having moved to three different countries - without embracing technology.

I can’t imagine my life without Google translate, online maps, search, cloud calendars and messaging apps.

But what I am saying is this: With every step forward in technology there is a trade-off.

With digital cameras, you get to see what you’re shooting instantly, you can adapt, you can improve on the fly. You save money and time.

But with film cameras you might get a more interesing result, more refined, better composed, more creative.

With word processing on a computer, you may gain speed and save your fingers. But with a typewriter you get a different, more refined product.

A tool is not just a tool

The nature of the tool we use to make something has a direct result not just on the nature of the product, but also on its quality, because of the way it forces us to work.

The advent of a tool can also lead to over-reliance on such a tool, as people get excited about its potential. Remember what Maslow said about the hammer? Now, apply this to the 1990s when Photoshop 1.0 came into existence.

If Maslow lived in the 90s, he might have said, with the gradient tool in my hand everything looks like a psychedelic trip.

The human factor

The tool is nothing without the human. We give them meaning and in turn they shape the world around us. They make our ideas come to life. But we need our conciousness and our awareness to be sure we don’t become overly reliant on them, and that they don’t blunt some of the parts of our brains that keep us sharp.

Take online maps for example. If you become overly reliant on them, you don’t get to know your environment. You are not grounded in your physical surroundings. If you don’t sometimes get lost you miss out on experiences, your life becomes too rigid.

And your phone remembers all your contacts phone numbers. Does that blunt our memories?

Your online calendar keeps your life in sync. But I will tell you something from my own experience. I have ADHD and that means I struggle with time blindness. And I have started to learn that digital calendars don’t help me be more organised. I used to work with a colleague who drew her monthly calendars with a ruler and pen to plan the next few weeks. I used to joke with her asking if she knew that Outlook could do this for her, but now I see the value, for somebody like me with time blindness, in taking a pen and paper, drawing, visualising your time so that it gets locked in through the experience of drawing it and writing it.

The ai-lephant in the room

I for one have been amazed at the power of AI. Especially ChatGPT’s capabilities are mindblowing. We are making leaps with this technology that I didn’t think I would even see in my lifetime. And yet, here we are.

This is one of the most exciting times in history to be a creative professional.

But, it is just another tool. And I think we also have to ask ourselves: what does it take away? What is the trade-off?

Recently I asked it to simplify a long document into a short summary and it did it brilliantly. It is such a time saver. But the ability to summarise long text is an important skill for writers. Moving the words, thinking about the essence, it is all making the writing muscle stronger.

If I was a new writer, I’m sure I’d be tempted to use this kind of time saving ability all the time. But would I still develop the right writing muscles?

I am excited for what technology like generative AI can bring, but want to propose that remain conscious of what it can take away.

I want to end this rather long post where we began. With Maslow’s pyramid.

Look at it. At the bottom is just us, our physiological needs. But with our tools, we have been able to meet our needs and finally, at the top, we are able to actualise. To be who we are meant to be.

And now, more than ever, we need to be aware that the tools that we find at the top of the pyramid don’t make us slide all the way back down to the bottom.